Erlang error handling primitives

August 17, 2016

Defines Erlang’s error handling terms and rules and then demonstrates how the primitives work with simple examples in the Erlang shell.

Erlang … takes the approach that failures will happen no matter what, whether they’re developer-, operator-, or hardware-related. It is rarely practical or even possible to get rid of all errors in a program or a system. If you can deal with some errors rather than preventing them at all cost, then most undefined behaviours of a program can go in that “deal with it” approach.

This is where the “Let it Crash” idea comes from: Because you can now deal with failure, and because the cost of weeding out all of the complex bugs from a system before it hits production is often prohibitive, programmers should only deal with the errors they know how to handle, and leave the rest for another process (a supervisor) or the virtual machine to deal with.

Given that most bugs are transient, simply restarting processes back to a state known to be stable when encountering an error can be a surprisingly good strategy.

There are four basic terms to understand.

In Erlang, you build a system by linking processes together. Instead of thinking in terms of classes, think in terms of processes. Processes only communicate via messages and signals and do not share memory.

Erlang error handlingMost of the Erlang information in this post comes from the excellent An Erlang Course, (1999) by Joe Armstrong and Ericsson. It’s not long, I recommend you check it out. mainly deals with how processes communicate errors to each other. Here are the basic terms:

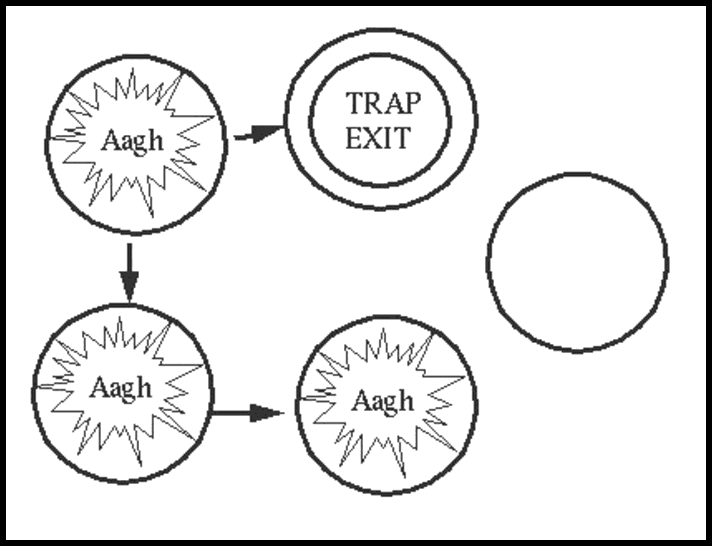

- link: A bi-directional propagation path for exit signals between processes.

- link set: The set of all links to a process.

- exit signal: Process termination information.

- error trapping: The ability of a process to process exit signals as if they were messages.

Wait, what is the difference between a message and an exit signal?

Messages go to a processes mailbox. Every process has a mailbox and the address for that mailbox is the process id.

For example, here we spawn a process that waits for a message. The process id is <0.60.0>. We send the process a message with the bang (!) symbol, and the process prints the message. The process then stops of it’s own accord (because there is no loop statement at the end of the receive clause).

~$ erl

Erlang/OTP 19 [erts-8.0.1] [source-ca40008] [64-bit] [smp:8:8] [async-threads:10] [hipe] [kernel-poll:false]

Eshell V8.0.1 (abort with ^G)

1> PrintMessageThenExit = fun() -> receive M -> io:format("Got message ~p~n", [M]) end end.

#Fun<erl_eval.20.52032458>

2> spawn(PrintMessageThenExit).

<0.60.0>

3> Pid = lists:last(processes()).

<0.60.0>

4> Pid ! hello.

Got message hello

hello

5>

Exit signals only travel on links and will use the mailbox only if the process at the other end of the link has turned on error trapping.

More examples follow below.

The exit signal propagation rules.

- When a process terminates it sends an exit signal, either normal or non-normal, to the processes in its link set.

- A process which is not trapping exit signals (a normal process) dies if it receives a non-normal exit signal. When it dies it sends a non-normal exit signal to the processes in its link set.

- A process which is trapping exit signals converts all incoming exit signals to conventional messages which it can receive in a receive statement.

- Errors in BIFs or pattern matching errors send automatic exit signals to the link set of the process where the error occurred.

The erlang shell is a process.

1> erlang:processes().

[<0.0.0>,<0.3.0>,<0.6.0>,<0.7.0>,<0.9.0>,<0.10.0>,<0.11.0>,

<0.12.0>,<0.14.0>,<0.15.0>,<0.16.0>,<0.17.0>,<0.18.0>,

<0.19.0>,<0.20.0>,<0.21.0>,<0.22.0>,<0.23.0>,<0.24.0>,

<0.25.0>,<0.26.0>,<0.27.0>,<0.28.0>,<0.29.0>,<0.33.0>]

2> self().

<0.33.0>

3> q().

ok

4> ~/src/erlang-sandbox$

The shell process dies and restarts when it receives an exit signal.

This is a special property of the shell process. You can tell the shell restarted because it’s process ID changed.

1> self().

<0.33.0> % The process id of the shell starts as 0.33.0.

2> 1/0.

** exception error: an error occurred when evaluating an arithmetic expression

in operator ’/’/2

called as 1 / 0

3> self().

<0.36.0> % The process id of the shell has changed.

4>

If the shell spawns but does not link to a process that dies, the shell does not die.

The shell is not linked to the process it spawned, so it does not get the exit signal from it’s child. The reason the shell sometimes starts as process id 0.33.0 and other times as 0.57.0 is due to running this code under different versions of Erlang. The 0.33.0 corresponds to Eshell V7.2.1 and the 0.57.0 to Eshell V8.0.1.

~/src/erlang-sandbox$ cat crasher.erl

-module(crasher).

-compile([export_all]).

countdown(N) when N == 0 ->

exit(boom);

countdown(N) when N > 0 ->

io:format("child~p~n", [N]),

timer:sleep(1000),

countdown(N - 1).

1> c(crasher).

{ok,crasher}

2> self().

<0.33.0>

3> spawn(crasher, countdown, [2]).

child2 % countdown/1 output.

<0.41.0> % spawn/3 return value is child pid.

child1 % countdown/1 output.

4> self().

<0.33.0>

5> spawn(crasher, countdown, [-2]).

<0.44.0>

6>

=ERROR REPORT==== 19-Feb-2016::07:14:57 ===

Error in process <0.44.0> with exit value:

{function_clause,[{crasher,countdown,[-2],[{file,"crasher.erl"},{line,4}]}]}

self(). % The sixth command is pushed down by exit output.

<0.33.0>

7>

If we link the shell to it’s child, then the shell dies.

The exit signal travels across the link to the shell process.

1> self().

<0.33.0>

2> link(spawn(crasher, countdown, [2])).

true

child2

child1

** exception error: boom

3> self().

<0.38.0> % The shell has new PID, so it crashed and restarted.

4> link(spawn(crasher, countdown, [-2])).

** exception exit: function_clause

in function crasher:countdown/1

called as crasher:countdown(-2)

=ERROR REPORT==== 19-Feb-2016::07:19:01 ===

Error in process <0.40.0> with exit value:

{function_clause,[{crasher,countdown,[-2],[{file,"crasher.erl"},{line,4}]}]}

5> self().

<0.41.0>

6>

Unless the error signal is a normal one!

$ cat normal_crasher.erl

-module(normal_crasher).

-compile([export_all]).

countdown(N) when N == 0 ->

exit(normal); % The exit message is the atom "normal".

countdown(N) when N > 0 ->

io:format("child~p~n", [N]),

timer:sleep(1000),

countdown(N - 1).

$ erl

Erlang/OTP 19 [erts-8.0.1] [source-ca40008] [64-bit] [smp:8:8] [async-threads:10] [hipe] [kernel-poll:false]

Eshell V8.0.1 (abort with ^G)

1> c(normal_crasher).

{ok,normal_crasher}

2> self().

<0.57.0> % Shell starts as process id 0.57.0.

3> link(spawn(normal_crasher, countdown, [2])).

child2

true

child1

4> self().

<0.57.0> % Same process id for shell, so no crash.

5>

If we trap the exit signal, the shell receives the signal as a message and does not die.

Continuing shell session from above …

6> process_flag(trap_exit, true).

false % process_flag/2 return value

7> link(spawn(crasher, countdown, [10])).

child10 % countdown/1 output

true % link/1 return value

child9

8> receive X -> X end. % shell blocks waiting for a msg

child8

child7

child6

child5

child4

child3

child2

child1

{’EXIT’,<0.45.0>,boom} % shell got an EXIT message

9> self().

<0.41.0>

10>

Further Reading

As mentioned above, the An Erlang Course, (1999) by Joe Armstrong and Ericsson is a concise introduction to these same topics and gives more detail.

If you want to go even deeper, read The Zen of Erlang, by Fred Hébert. It covers monitors and details how to use the OTP supervisor behavior to build reliable systems.

Change Log

Sep. 17, 2016

- Display id that comes after #Fun in interpreter output.

Tags: erlang